The Exchange: Susie Linfield on Photography and Violence

November 22, 2010

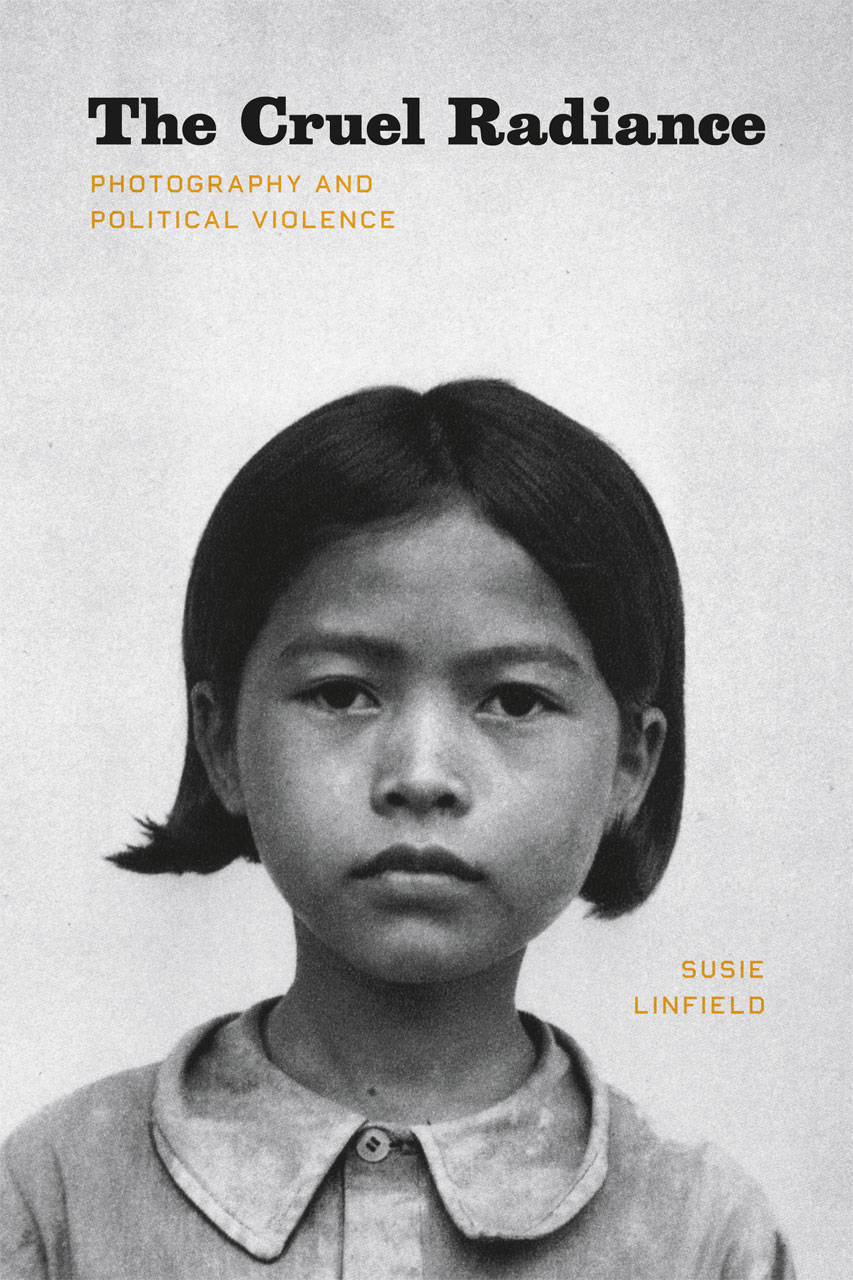

Do photographs provide our most immediate connection to truth, or do they confuse, mislead, or tell outright lies? In “ The Cruel Radiance: Photography and Political Violence ,” out now from the University of Chicago Press, Susie Linfield examines what photographers and the images they capture can tell us about the human catastrophes of the modern age—from the Warsaw Ghetto and Auschwitz, to China during the Cultural Revolution, to more contemporary locations of violence and oppression: Sierra Leone, Sudan, Afghanistan, and Abu Ghraib. Linfield , an associate professor of journalism and director of the Cultural Reporting and Criticism program at New York University (of which, to note, I am a graduate), takes on the questions: “Can photography itself make the world more livable? Can it justify its claims to give a voice to the silent and expose the plight of the powerless?…can it illuminate the dark?”

You write that for many critics “photography is a powerful, duplicitous force to defang rather that an experience to embrace and engage.”

Photographs start becoming a mass form, and start being written about as a mass form, in the Weimar Republic, which of course was the most crisis-ridden moment of modernity—and a prelude to utter catastrophe. For some very good reasons, photographs were seen by some of the Weimar writers—and especially by some of the Frankfurt School critics—as a kind of opiate of the people: as a form that couldn’t really explain the political contradictions, a form that appealed only to sentiment and not to the intellect. Siegfried Kracauer, for instance, warned that “the image-idea drives away the idea.” And Brecht, who I think of as a kind of father-figure, or superego, of the Frankfurt critics, loathed photographs; he regarded them as a form of sentimentality, as a barrier to political knowledge.

This suspicion, even dislike, of photographs was absorbed by many subsequent critics, including Susan Sontag and Roland Barthes; and certainly by the postmodern critics who came after them. Of course, that kind of skepticism and suspicion can lead to certain

insights; but at a certain point, it also occludes. The Frankfurt-Sontag-postmodern critique has made it too easy for us to not look at photographs. We’re so afraid to look—we fear that looking is voyeuristic, that it’s exploitative, that it’s a cheap form of knowledge. Not-looking has been endowed with a kind of moral sanctity and intellectual respectability, which I don’t think it deserves.

Why does photography cause such anxiety?

Photography is a kind of mechanical reproduction, as Walter Benjamin famously wrote, and we often have a great suspicion of the mass-produced. Photography has become a magnet for a lot of anxieties: about politics, modernity, mass culture. And photography is something that anyone can do: they might not do it well , but anyone can pick up a camera. These days, with cell phones, everyone in the world is a photographer, which is an interesting phenomenon.

Most arts—think of music, dance, theatre, painting, literature—take much more forethought, training, and technical discipline than photography does. (Although I think the great photographers do have technical expertise, and often years and years of experience, which allows them to take that seemingly instantaneous photograph that will mean something.) Photography is a completely different kind of art—if it even is an art, which has always been disputed. And a completely different kind of journalism, if it is journalism. In fact, we’re still not at all sure what photography is: is it news, art, entertainment, documentation, science, or surveillance? It tends to blur all those boundaries, which is exciting, but also bewildering and confusing.

Photography is also more often associated with ideas of morality than the other arts—for the photographer, his or her subjects, and the viewer.

Since a photographer is there at the moment that something happens—and, often, at the moments when horrible things happen—all kinds of ethical problems emerge. Did the event happen for the camera? Would it have happened if the camera wasn’t there? Should the photographer have intervened? Are we complicit in looking?

This raises the question of intent. There’s a whole school of criticism that argues that we shouldn’t look at photographs that were taken by Nazis: that these are photographs taken by the murderers, that the photographs themselves were meant to humiliate the victims, that they represent exploitation and cruelty. And, of course, all this is true. But photographs often say things that their makers do not intend, and some of these Nazi photographs reveal the suffering of the victims in very powerful and evocative ways. They also reveal the cruelty of the perpetrators, which is something that I think we should look at. We shouldn’t be afraid that in looking at an exploitative photograph, we become the criminals: that’s a kind of magical thinking. On the contrary, we may see the insanity of the perpetrators far more clearly than ever before, and certainly more clearly than they ever saw themselves.

Although they are not equivalent, in some ways the photos from Abu Ghraib are like the Nazi photographs, because the Abu Ghraib images, too, were taken to humiliate the victims. They are horrific images, because they depict a horrific reality. But I think it is good that those photographs became public. We as Americans needed to see those photographs.

We’ve spoken about the limitations of photography. What are some strengths of the form?

One of the things that photographs do is bring us close—closer than anything else I can think of—to physical suffering and to bodily harm, to what Elaine Scarry called “the body in pain.” People often talk about the horror of war, and about the necessity of building a politics of human rights, in extremely abstract terms. I think we need to engage, far more concretely, a series of questions: What does war actually do to people? What does political oppression, defeat, physical suffering do? How are people broken? Perhaps that’s an uninspiring and un-triumphant approach, but it may be one that we need. The Iraqi writer Kanan Makiya writes about this in his book “Cruelty and Silence”—about the need to understand the substance of cruelty rather than waving around abstract ideas of national liberation and human rights. We need to understand the horrific histories that we have inherited, and that continue to be made. And for me, photographs are a way into those realities in ways that are truly sui generis.

Of course, photographs can’t explain the complexities of these histories or their causes. Photographs are powerful glimpses, powerful hints . I make a plea, in my book, for viewers to become more proactive—instead of endlessly whining about all the things that photographs can’t do and don’t tell us, and all the ways that they are too superficial, etc. Some of that may be true. But it’s up to us to begin to investigate these histories, and to learn what it is these photographs are saying.

The photograph on the jacket of the book is especially arresting and expressive of the dilemmas inherent in interpreting images.

The cover of my book is a photograph of a young Cambodian girl before she was executed, and probably tortured, by the Khmer Rouge as a so-called enemy of the state. Looking at that photograph could not tell me all or most of what I needed to know about the rise of the Khmer Rouge and their genocidal politics. But it offered me a way into the lunacy of that political regime. We can know the numbers—that an estimated two million Cambodians were killed—but to begin to really think about what it means for a government to torture and execute its own children is, I think, something else.

It’s been interesting to observe reactions to the cover. The girl in the photograph is startling in her implacability, in her dignity and self-possession. People are very drawn to her, aesthetically. But when I tell them the facts behind the photo, they recoil in horror. And this points to something crucial: the importance of context. Walter Benjamin made a strong plea for words—he thought that words, captions, would save photographs from being misunderstood or misleading. Of course, you need more than just a caption to explain the Khmer Rouge. But context is very important.

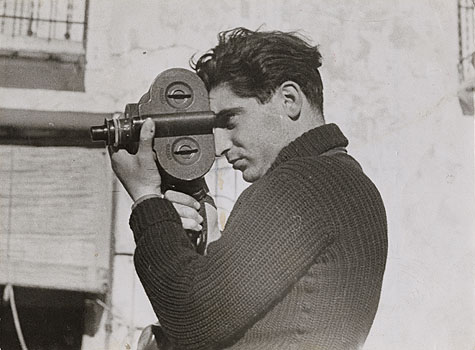

You devote several chapters in your book to the morally complex work of iconic war photographers—Robert Capa, James Nachtwey, Gilles Peress—each of whom have ardent admirers and fervent detractors.

In a way, the hero of my book is Robert Capa (and his colleague Chim). Capa’s tenderness and admiration for the people he was photographing—in the Popular Front in Paris, in the war in Spain, in the Israeli war of independence—was so palpable. His photographs brim with love (and anger). But I don’t think those kinds of photographs can be taken anymore.

Capa was the iconic war photographer of his time. James Nachtwey is the iconic war

photographer of our time—but unlike Capa, Nachtwey is accused of being a pornographer, an exploiter, a voyeur. On the other hand, someone like Sebastião Salgado, who takes a more overtly humane and respectful approach to his subjects, is accused of being too sentimental. I write in the book about this Catch-22 in which contemporary photojournalists are caught: When photographs are very brutal, very explicit in depicting violence, the photographers are accused of re-victimizing the victims. When they take a different approach, which is a respect for the resilience and even beauty of oppressed and exploited people, they are accused of being evasive, romantic, and condescending. In my view, the fact that both these approaches are so harshly criticized is a sign of a far more generalized resistance to the very act of looking—and, therefore, to thinking about certain things.

In addition to the moral particulars for the photographer, the viewer faces his or her own dilemmas when looking at photos of violence, pain, and suffering. And one of those dilemmas, as you write, centers on the unpredictability of our reactions.

We often don’t have the “right” reactions to photographs of violence and oppression. This is certainly true for me. Sometimes you feel irritation—victimhood can be irritating. Sometimes you feel contempt or disgust. Photographs of suffering and violence do not always call up empathy and solidarity. Some such photographs—especially today, when we often lack the political context in which to understand these conflicts—actually call up anti -solidarity. It’s very bewildering to look, for example, at photographs of child soldiers. They are victims of horrific crimes—they are kidnapped, beaten, raped, starved. But they are also criminals. They have been trained to be killers, to be sociopaths, and they themselves are guilty of rape and murder and mutilation. In some photographs, they seem to be taunting the camera, challenging the viewer. They seem to be revelling in their warrior status. It’s very conflicting to look at those pictures; I have no idea what I “should” feel. The same is true of looking at some of Nachtwey’s photographs, especially of those documenting the man-made famines in Somalia and Sudan, where people were withered, almost beyond recognition, into near-nothingness. Those photographs are shocking and repulsive, and they raise Primo Levi’s question about Auschwitz: “If this is a man.”

So photographs are very good at conjuring up a conflicted stew of emotions. But rather than censor ourselves, we should allow ourselves to experience the photographs, and then analyze what those reactions mean. We need to look at these images with a more open mind and a more open heart, and allow ourselves a free reign. Then we need to do the analytic work, the historic work, the political work. Emotion is not an endpoint—I too am a Brechtian in some ways!—but it can be the starting-point to investigating what it means to be a victim, what it means to be defeated, what political oppression does. Photographs illuminate the terribly damaged family of man to which, I’m afraid, we all belong.