Vreni Hockenjos is a film and media researcher. One of her main focuses is the history and development of the photobook. She completed her doctorate at Stockholm University on the interaction between literature and visual media around 1900 (Picturing Dissolving Views, 2007). Numerous publications on the subject, including in Fotogeschichte, PhotoResearcher and anthologies. She is part of the REFLEKTOR group and curates exhibitions and events related to photography.

Kurt Lhotzky (K.L.): From 2nd to 5th November 2023, the 10th Photobook Week Aarhus (PWA) took place. Can you tell us a little bit about this now already traditional event?

Vreni Hockenjos (V.H): The Photobook Week in Aarhus, Denmark is small but nice. This was the second time I’ve been there and it’s very personal because most of the visitors watch the whole program, so there’s a lot of time for exchange among each other. What I particularly appreciate about the festival is how diverse the exhibitions and talks are; there is a lot to discover that I had no idea about before, such as photo novels from Africa! In addition to exciting new artists, Aarhus is one of the few festivals that also looks at the history of the photobook.

K.L: With Thomas Wiegand you curated the exhibition “For Kids Only?! Exploring Photobooks for Children” as part of the PWA and in collaboration with the Herning Museum of Contemporary Art. How did this collaboration come about?

V.H.: I had been working on children’s books about photography for several years and Moritz Neumüller, the chief curator of Photobook Week, then asked me if I wanted to do an exhibition about photobooks for children together with Thomas Wiegand. Thomas Wiegand has a large collection of photobooks, not just children’s books, but since he initiated an exhibition in Kassel a few years ago about Bullermax (1964) – a great photobook from the GDR by Edith Rimkus – he has also looked more closely into children’s books. Working together with him on this not really small and yet very little researched topic was a great experience.

K.L: At least in Austria, photobooks for children – and I’m not thinking of manuals like “My First Selfie” – have played a surprisingly small role. I can also remember heated controversies in the 1980s about whether early picture books with photos for infants were even educationally recommended. Was this a “regional peculiarity” or a general topic of discussion?

V.H.: I think that these discussions were not only limited to Austria. Of course, if you go to a bookstore today – no matter where: the vast majority of picture books have drawings – very few have photos, and if there are photos, then they are pretty „boring“ in the non-fiction section. Why photos never really caught on is a very good question that I would like to know the answer to myself! What we were able to show in the exhibition is that there are wonderful children’s books that are illustrated with photos, and have certainly been doing so since the 1930s, if not earlier. And photos are not only represented in the non-fiction area, but have been used in very different and creative ways. As far as first picture books are concerned, it is fascinating that there are still to this day relatively many that work with photographs. Perhaps one of the most famous photo books for children is just such a book for small children: My First Picture Book (1930) by Mary and Edward Steichen. Edward Steichen was already a renowned photographer back then and his daughter Mary was very interested in modern reform education, so she approached her father with the idea of taking 24 photos from the typical everyday life of small children. At that time, Mary Steichen consciously decided to use photographs because they could give the child a more “objective” picture of an object than drawings, which were “subjectively” distorted by an illustrator. So the argument was exactly the opposite to that in the 80s!

Personally, I can’t see that one or the other would make more sense from an educational point of view, it really depends on how the images are made, i.e. whether they have a clear structure and clear colors and are not overloaded.

K.L: We are usually very focused on what we know. The former GDR and the Eastern European countries are still a little under the radar. What did it look like there?

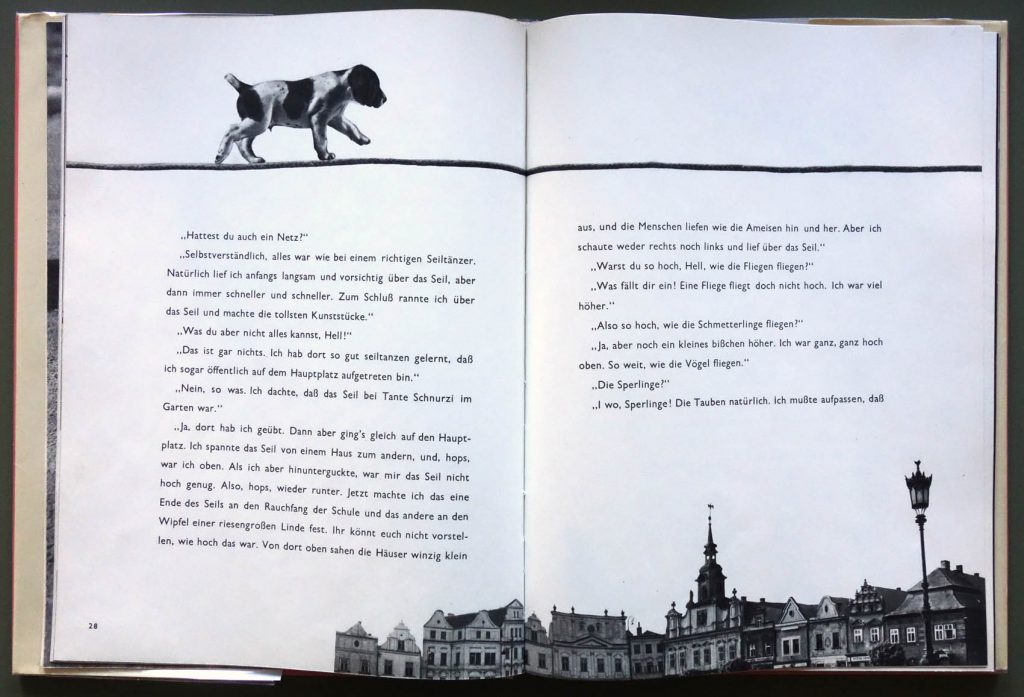

V.H.: Thomas Wiegand did a lot of research in this area for the exhibition and I was able to learn a lot from him. Especially in the 1950s and 60s, a large number of very beautiful photographically illustrated children’s books were produced in the former Eastern Bloc countries. That was quite a heyday, not least because the production of these books was expressly approved by the state. The books were often exported to the West in order to obtain urgently needed foreign currency. Some books were even first produced in German, i.e. for export, and only later translated into the country’s own language. This is what happened, for example, with the wonderful Czech children’s book Vom lügenhaften Hündchen (The Lying Puppy) (1962) by Jan Lukas and Emanuel Frynta.

K.L: There seem to be a few projects running internationally that focus on photobooks for children from a media-historical and media-theoretical perspective…

V.H.: Right. A lot has changed in the last year or two. For a long time, there was hardly any interest in children’s books among photobook researchers. But several research symposiums have now been held, and important new impulses are coming from children’s literature research in particular. For example, a first anthology on the topic, by Laurence Le Guen has just been published – albeit in French – in which she looks at a selection of photobooks for children from the last 150 years. It is also Le Guen who is curating an exhibition on the same topic at Maison Doisneau, which will open in the spring 2024. In general, France is very active when it comes researching photobooks for children. Anne Lacoste from the Institut pour la photography in Lille, for example, is also leading a larger international research project that I am very excited about.

K.L : What do you think is the current status – is the photo picture book on the rise or still a niche product? And – what are things that are still lacking, in your opinion?

V.H.: Well, I doubt that photography will one day catch up with drawn pictures in children’s books or even surpass them! Of course, that is not necessary either. However, I do believe that interest in photographic illustrations in children’s books has increased recently. It is significant, for example, that the most important fair for children’s books, in Bologna, has created a new category for photography for their awards last year. One of the most renowned German photobook publishers – Steidl – has also started its own section for children called “Little Steidl”. What makes me happy is that photography is no longer just purely documentary, but rather versatile and creative, for example in the form of collages, so that it is increasingly being used as an artistic choice.

As far as shortcomings are concerned, maybe we’ve come full circle a bit now, because I actually became interested in photobooks for children in the first place because I was looking for a good children’s book about photography. There are lots of practical guides for children – how do I take better photos or what cool projects can I do with the help of photos. But there isn’t a single one – at least I don’t know of one – that presents the history of photography for children in a fun, engaging way, like many great children’s books about art and art history do. That’s why I decided some time ago to take matters into my own hands and write exactly the kind of book I would want for my daughter. Now all I have to do is to find a publisher, so please keep your fingers crossed!

About the photos used:

The featured image shows Vreni Hockenjos with a book by Viennese photographer Christine Werner, which is not a children’s book. Creative Commons Licence: Kurt Lhotzky

The photos from „My first picture book“ and „Das lügenhafte Hündchen“ as well as from Herning: Copyright Thomas Wiegand